Humans typically integrate traumatic events into workable experience in the same way we do non-traumatic events — by feeling, thinking, and talking our way into and through the memories of them. Whether we loathe or welcome the process, through listening to songs that “take us there,” through conversations and contemplations that directly reference the attack, even through jokes and nightmares that poke or stab at the heart of the loss or humiliation, we tend to relate to our traumas.

As creatures geared toward balance and healing, sense and meaning, we are inclined to have this kind of flexible relationship with everything that happens to us. We therefore experience ever-maturing, adaptive shifts in our present view of the past. Attention and awareness lead to insight such that we can make meaningful use of whatever has happened. We can live with it, not despite it. We can move forward constructively from it. A difficult past won't ever be changed of course, and need not be prettified, but will become workable — for some people even motivational — if we and our supporters can relate to it.

In the case of unprocessed trauma, the ability to relate to past traumatic events is not yet developed or supported. Whether it’s a week or a decade post-trauma, for the PTSD sufferer, the memories of a senseless event are as sharp and vivid as the original experience of it. Without support, the traumatized man, woman, or child can’t approach those memories let alone integrate or make sense of them.

Instead he lives in two worlds:

One world is surreal and full of people who want him to be ok, need him to get back to normal, think he should move on. The other world is the real one, the one that stopped when the trauma started. That world is comprised of the preserved sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and feel of the trauma along with a deeply felt strong ongoing sense that something very bad is very close.

Who wouldn’t want to wall off an unbearably real world of events that cannot but must be acknowledged and integrated, a world of happenings that can't have happened but did, and put it away in favor of a world that he and everyone who loves him wishes still existed?

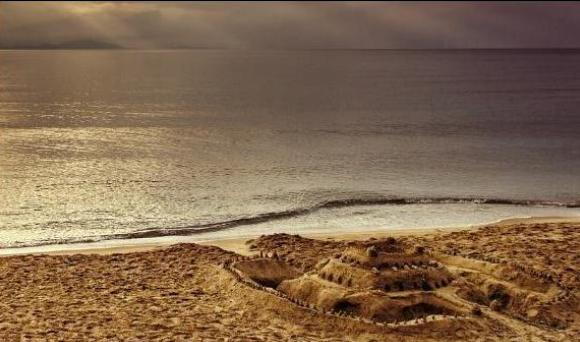

Picture a sand castle, one of those award-winning ones with sharp corners and intricate details. Now construct a barrier around, above, and beneath it with whatever kind of material you think is indestructible. The barrier will keep creatures, waves, and weather from it. Whenever you happen to glimpse that castle, whether daily or decades from now on your deathbed, it will appear intact. Nature should’ve worked on it, elements and creatures should’ve worn it down, but the barrier has kept the castle pretty much how you left it.

For the PTSD sufferer, the castle is, of course, the traumatic memory. The barrier around it includes various substrates of a single devastating obstacle to trauma processing: the sufferer cannot relate presently or safely with her memories of a real event.

The child or elder abuse was not shared... The college rape was not reported... The commanding officer was not knowledgeable or assertive about PTSD treatment... The financial or emotional needs of family overwhelmed the sufferer’s need for treatment... The protocol offered was not trusted or effective... The treating clinician was not properly trained...

The trauma therefore cannot be met, let alone be related to and resolved. It is segregated, wanted desperately to be gone, and in that way, denied and preserved.

In truth we can’t completely or permanently segregate, can’t effectively get rid of, anything we’ve experienced. The denied memory, the walled-off castle, will passively degrade and leak into the surrounding environment, impacting everything around it in sometimes subtle, sometimes disastrous ways despite all efforts to compartmentalize it.

But for a PTSD sufferer whose castle is a nightmare that actually happened, walling it off and keeping it out of the mind’s eye (even via extreme measures like sedation and sleeplessness*) seems like a damn good idea.

Those leaks of traumatic material are flashbacks, uninvited-therefore-intrusive glimpses of an intact trauma memory. One of many problems with flashbacks is that their triggers are not always known, and so are not easily avoidable. The green water bottle on your desk could send your office mate into a panic attack or dissociative state because something like it was in her view before, during, or after the moment she was attacked five years ago. For you, it’s a green water bottle. For her, it’s retraumatization, and it reflects and perpetuates the tragic preservation-through- avoidance of traumatic material.

Though PTSD treatment strategies and protocols differ in how much exposure to traumatic material is necessary for resolution to occur, they all aim to make the client’s references to past events approachable in the present so they can be recognized by the client as not actually recurring, as not so close or inevitable — as workable even if at some level forever troubling. Easier said than done.

Relating to trauma flexibly and confidently is a gradual and uncomfortable process that usually depends on someone other than the PTSD sufferer being able to do it at first, i.e., a psychotherapist who is trauma-trained and trusted.

At first, it is the therapist who provides a calm, safe container in which the existence of a client's trauma can be bravely met and gently (indirectly and non-specifically) explored. As the client masters self-regulation skills to manage the anxiety that will arise as he orients to the memories, specific details of the trauma can also arise and be navigated more readily in the client’s private experience, even if not discussed in explicit detail with the therapist.

Through a therapeutic relationship that includes privacy and dialogue around traumatic material, the client grows in confidence, recognizing himself as a trustworthy, reliable, capable container for his own shifting experience. Now a spontaneous mixing and mingling of previously siloed material can and will occur — of bad memories and good, of grief and possibility, of personal experiences and others’ experiences, of a dark past that really happened and a rising-sun of a future.

The castle, the dysfunctional testimonial to a PTSD sufferer’s unbearable but real experience, is now seen and felt and crumbling — never completely unhad, but softened by a gull’s landing, by rough and gentle waves of reference, by the winds of anger and probably at some point a ready rain of tears. PTSD that is exposed to the brave and spacious care and sense of the client’s natural ability to heal, and those who support that healing, simply cannot help but resolve.

*Sedation, though certainly not a goal, can be achieved by way of prescribed psychiatric medications, especially in the absence of concurrent psychotherapeutic support, as well as self-medicating with legal or illicit substances. Sleeplessness, also not a goal, is achieved by way of the anxiety and hypervigilance that mark a PTSD sufferer's days and are especially heightened at night, when she is asked to enter a sentient being's most vulnerable state of mind and body: sleep.